Every generation seems to get the scandalous, headline-grabbing art exhibition it deserves. The most recent one is Documenta 15 in 2022, which was so controversial that there may never be a future edition of the show in Kassel, Germany. There is also, of course, the 1993 Whitney Biennial, which introduced so-called identity politics into the mainstream discourse of art. Going back even further, there was the 1913 Armory Show in New York, the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874, and the 1865 Paris Salon, where Manet’s Olympia created a stir.In all of these cases, it was the art on view that generated uproar, not the forces behind the exhibitions themselves. A different situation unfolded at the 1964 Venice Biennale. The show is remembered, not always fondly, for Robert Rauschenberg having taken home the exhibition’s Grand Prize for Painting (the precursor to today’s Golden Lions)—a choice that some said smacked of corruption among the jury and other insiders who meddled with it. anginqq

Taking Venice, a new documentary out next month in limited release, wants viewers to revisit this history, forgotten in many ways because of the outsize role that Rauschenberg and his cohort have since assumed in the canon of art history.

The documentary points out that because the United States has never had a Ministry of Culture, as many European countries do, the country’s pavilion in Venice is an anomaly. It was built not by the US government but by philanthropist Walter Leighton Clark and his artist co-op Grand Central Art Galleries before ownership was later transferred to various museums over the years. The 1964 Pavilion, however, was the first to be organized by a government entity, the fine arts division of the United States Information Agency (USIA). It was the height of the Cold War after all, and the US was in it to win it, aiming to ensure the triumph of liberal democracy over Communism. Culture then would be an extension of that, soft power avant la lettre.

Enter the commissioner, the insider, the dealer, and the artist. Those are the codenames that art critic Amei Wallach, the film’s director, gives to Alan Solomon, the groundbreaking curator who at that moment was heralded for transforming the Jewish Museum into supporting the avant-garde; curator Alice Denney, a friend of the Kennedys and the wife of a State Department intelligence researcher; New York gallerist Leo Castelli; and Rauschenberg, respectively. Taking cues from the spy genre, Wallach connects them in a web. anginqq

The intention of that group (minus Rauschenberg) was to ensure an American would win the Grand Prize, as none before had. “One of the intriguing subplots of the Biennale all through the decades, more than a century, has been how art and politics overlap. And it peaks—there’s a kind of high-altitude moment—with the American presence in 1964. It reverberates through history,” says Philip Rylands, a former director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. Artist Michelangelo Pistoletto (who appears on screen with a tag reading “he was there”) puts it more succinctly, “It was the crown American politics was missing.”

Denney dismisses those allegations, telling Wallach simply, “We didn’t cheat. We wanted to win the prize and show that we had some great art. And we thought with Rauschenberg we had a very good chance.”

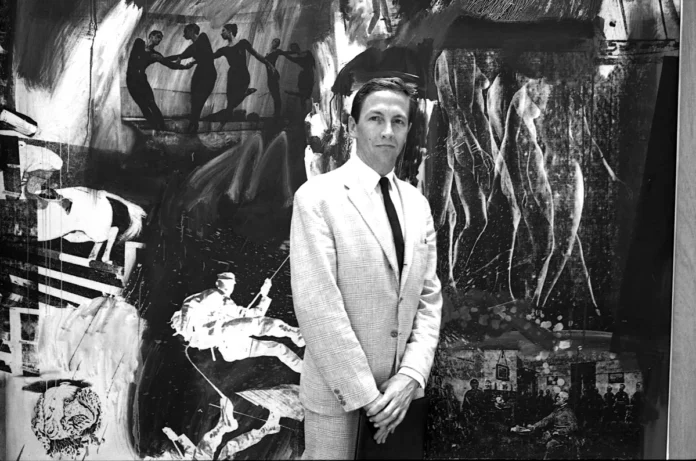

Transporting Robert Rauschenberg’s Express during the 1964 Venice Biennale.

PHOTO UGO MULAS/©UGO MULAS HEIRS, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Over the next 90 minutes, Wallach lays out the story of what happened, though for a documentary aiming to tell a clear history, the non-linear construction of the film is more than a bit befuddling, especially to viewers who haven’t been primed with a background on postwar art history.

To put it a bit more coherently, by 1964, Rauschenberg was on the cusp of wider acclaim, having already had his artistic breakthrough a decade earlier with his “Combines,” works that broke down the barriers between painting and sculpture. But his reception in New York wasn’t exactly welcomed. New Yorker staff writer Calvin Tomkins, who was also there, calls him the “bête noire of the American art establishment.” Rauschenberg, in an archival interview, himself admits that he was considered a “clown” and a “novelty.” anginqq